Joyful Life and Daily Practices

Joyful Life and Daily Practices

- Article of ALOK MIND (Buddhist Psychology) No. 1.

- Author: Bhikkhu ALOKA

- Published by ALOK MIND Foundation

- Issued: 1 October, 2023

Abstract

This academic paper investigated the origins and impacts of common psychological problems in human life. Drawing from Buddhist philosophy and psychological insights, it explores how negative thought processes can give rise to issues such as excessive selfishness, unhappiness at others’ success, jealousy, dissatisfaction with life, and judgment. These problems are traced back to the root cause of negative thought (Ayoniso Manasikara), which can be considered the source of evil in the ultimate analysis.

The paper also studied the realm of negative emotional factors, identifying 14 such factors and their associated detrimental impacts. It highlights three negative emotional factors, namely conceit, jealousy, and avariciousness, which are directly opposed to Muditā psychotherapy or meditational techniques. Each of these negative emotional factors is dissected to reveal the four bad impacts they generate.

Furthermore, the paper explores the root of psychological problems, demonstrating how the belief in the self can lead to distorted concepts of self, body, and wealth. This distortion fosters excessive self-love, sensual attachment to the body, and an insatiable craving for wealth, ultimately driving individuals to seek recognition as the most beautiful, famous, or wealthy. Such pursuits often lead to negative mindsets, including a competitive spirit, conceit, and judgment, resulting in various psychological issues.

In response to these problems, the paper introduces Muditā meditation as a psychological therapy. Muditā, characterized by unselfish joy or sympathetic joy, is shown to be a remedy for emotional stress, anxiety, depression, and other forms of unhappiness. The paper also discusses the interconnectedness of four sublime ways of living, known as Brahmavihara: loving-kindness (Mettā), compassion (Karunā), unselfish joy or sympathetic joy (Muditā), and equanimity (Upekkhā), which collectively contribute to a peaceful and noble way of life.

Lastly, the paper emphasizes the importance of practicing Muditā meditation effectively and provides insights into evaluating one’s progress in this meditational technique. It underscores the transformation of the mind from reacting negatively to positive stimuli to responding with happiness and joy as an indicator of successful meditation.

Introduction

In the exploration of common psychological problems, this paper turns to the ancient wisdom of Buddhist philosophy and modern psychological insights. It begins by addressing the roots of these issues, revealing that negative thought processes, often fueled by selfishness, underlie problems such as unhappiness, jealousy, and judgment. These negative thought processes can be traced to the controversial notion that evil originates from negative emotions.

The paper proceeds to dissect 14 negative emotional factors and their associated detrimental impacts, with a particular focus on three factors directly opposed to Muditā psychotherapy. The examination of these factors sheds light on the intricacies of human emotions and their consequences on mental well-being.

Furthermore, the paper delves into the core of psychological problems, unveiling how misconceptions about self, body, and wealth give rise to excessive self-love and a relentless pursuit of external validation. This distorted worldview spawns negative mindsets and behaviors that contribute to various psychological issues.

The introduction of Muditā meditation as a psychological therapy provides hope for addressing these problems. By emphasizing unselfish joy and celebrating the happiness of others, Muditā offers a path to alleviate emotional stress, anxiety, depression, and other forms of unhappiness. The interconnectedness of four sublime ways of living, known as Brahmavihara, further contributes to a peaceful and noble way of life.

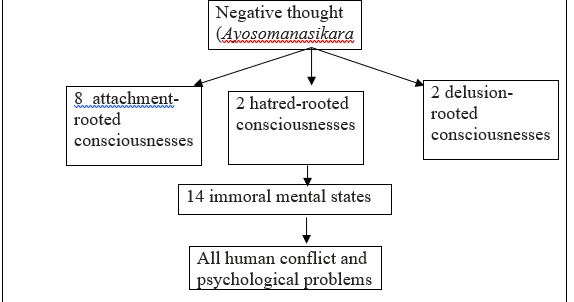

1. Emergence of Common Psychological Challenges

In the title of this paper, first and foremost, the author would like to clarify how human psychological problems arise. According to a Pali canonical text, Kathavatthu (Points of Controversy), human psychological issues, such as excessive selfishness, unhappiness at others’ success, jealousy, dissatisfaction with life, and judgment, originate from Negative Thought (Ayoniso Manasikara). Within the text, one of the points of controversy is, “Can negative thought be the root of evil? Yes (Akusalamūlaṃ ayoniso manasikaroto uppajjatīti? Āmantā).”[1] The controversial answer to the question was “Yes,” so it could be concluded that evil starts from negative emotions. In the ultimate analysis, the nature of the mind is pure, like cotton. However, when negative emotions enter the pure mind, it inclines towards the dark side. For example, just as natural cotton is white and pure, when a drop of black ink touches it, the cotton turns black or becomes impure. Similarly, unwholesome minds and mental states originate from negative thoughts (Ayonisomanasikara). Therefore, the root of the 12 unwholesome minds-eight attachment-rooted consciousnesses, two hatred-rooted consciousnesses, and two delusion-rooted consciousnesses is negative thought (Ayonisomanasikara). These 12 unwholesome minds are central to 14 immoral mental states or negative emotional factors, which include delusion, shamelessness, fearlessness, consequences, restlessness, attachment, misbelief, conceit, hatred, jealousy, avariciousness, worry, sloth, torpor, and doubt. All of these immoral minds and mental states contribute to human conflicts and psychological problems.

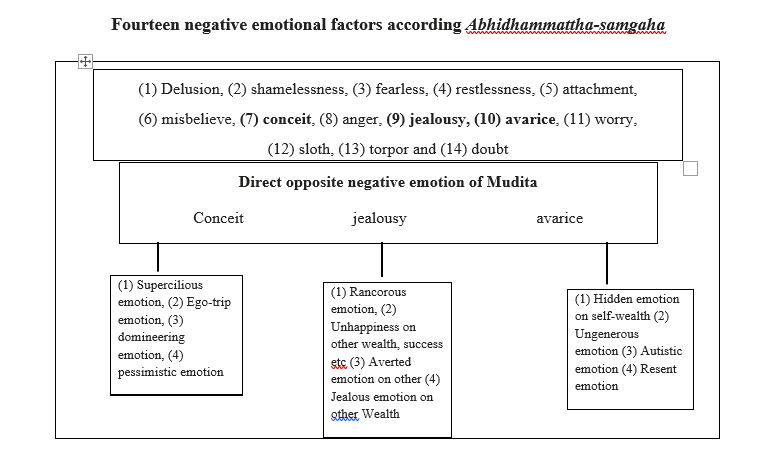

2. Fourteen Negative Emotional Factors and Bad Impacts

First and foremost, the researcher would like to elaborate on the title of this paper, which focuses on the directly opposing side of negative emotional factors, specifically Muditā, and its detrimental impacts. According to the description in Abhidhammattha-samgaha, there are 14 negative emotional factors:[2] Delusion, shamelessness, fearlessness, consequences, restlessness, attachment, misbeliefs, conceit, hatred, jealousy, avariciousness, worry, sloth, torpor, and doubt are among the 14 negative emotional factors. Out of these, three negative emotional factors stand in direct opposition to Muditā psychotherapy or meditational techniques, namely: conceit, jealousy, and avariciousness. According to Buddhaghosa’s Commentary, Atthasālinī,[3] Each negative emotional factor consists of four detrimental impacts. In the case of conceit, there are four negative impacts: (1) Supercilious emotion, (2) Ego-trip emotion, (3) domineering emotion, and (4) pessimistic emotion. For jealousy, there are four negative impacts as well: (1) Rancorous emotion, (2) Unhappiness regarding others’ wealth and success, (3) Aversion towards others, and (4) Jealousy regarding others’ wealth. In the case of avariciousness, there are also four negative impacts: (1) Hidden emotion regarding one’s own wealth, (2) Ungenerous emotion, (3) Autistic emotion, and (4) Resentment. These adverse effects of negative emotional factors contribute to psychological problems in human life. Additionally, these negative psychological factors can also lead to issues within families. This is why Prof. Dr. Sanu Mahatthanadull noted that “Psychological family problems indicate the presence of more psychiatric problems that can disrupt the nurturing relationship, such as maternal depression, social isolation, alcohol and substance abuse, domestic violence, etc.”[4] So, here the researcher would like to make clear by a diagram as the following:

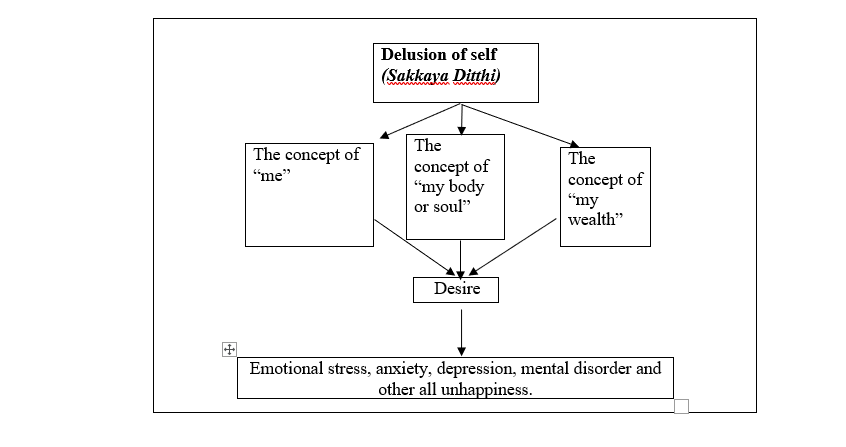

3. The Root of Psychological Problems

According to Buddhist psychological canonical text named Vibhangatthathā, human psychological problems including unhappiness starts from delusion of self (Sakkāya Ditthi)[5]. From the belief in the self, humans develop misconceptions about “me, my body, and my wealth.” By centralizing these erroneous concepts, humans develop excessive self-love. They sensually adore their bodies, consider their souls to be pure, and become consumed by cravings for wealth. These unfavorable ideas lead them to desire to be ‘the most beautiful or handsome,’ ‘the most famous,’ and ‘the richest.’ In their pursuit of these three goals, humans may develop a negative competitive mindset, conceit, pride, negative emotions, and judgmental attitudes. Individuals harboring these detrimental mindsets are likely to experience numerous psychological problems and misery in their lives.

To alleviate this miserable state, Lord Buddha provided a psychological therapy or natural remedy known as Muditā meditation. The essence of Muditā meditation lies in emphasizing unselfishness and finding joy in the happiness of others, which is why it is referred to as unselfish joy or sympathetic joy. Through the practice of Muditā meditation, practitioners can address their psychological problems, including emotional stress, anxiety, depression, mental disorders, and all other forms of unhappiness. Therefore, the researcher aims to clarify this through the following diagram:

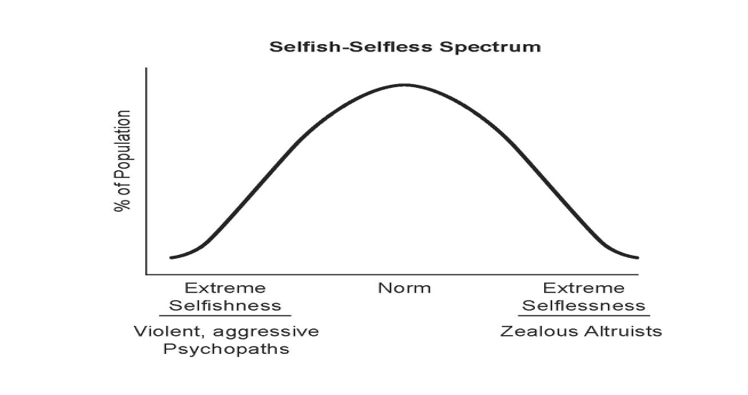

4. Modern Psychological Description of Selfish –Selfless Spectrum

According to the modern psychological selfish-selfless spectrum, individuals who exhibit extreme selfishness tend to display violent and aggressive psychopathic traits. Conversely, those who are extremely selfless are often fervent altruists.[6] The purpose of Muditā therapy or meditation technique is to diminish selfishness, as indicated by another definition of Muditā, which is unselfish joy. Therefore, Muditā therapy or meditation technique aims to reduce violent and aggressive psychopathic tendencies and to foster zealous altruism.

5. Joyful Therapy and Sublime Living

Individuals who engage in negative comparisons with others’ success or achievements may disregard their own accomplishments and perceive their successes as insignificant. Psychologically, such negative concepts can lead to unhappiness in human life. Therefore, as the Buddha stated in the Arati Sutta[7]“As stated by the Buddha in the Arati Sutta, in daily life, one should strive to live without dissatisfaction (Arati pahānāya), without violence (Vihimsa pahānāya), and without wrong livelihood (Adhammacariyā pahānāya). Instead, one should aim to live with sympathetic joy or satisfaction (Muditā bhāvetabbā), with non-violence (Ahimsā bhāvetabbā), and with right livelihood (Dhammacariyā bhāvetabbā).” In Buddhism, there are four sublime states of living (Brahma Vihara):[8]Loving-kindness (Mettā), compassion (Karunā), unselfish joy or sympathetic joy (Muditā), and equanimity (Uppakkhā) are the four sublime states of living. Those who embrace these sublime ways of living are likely to experience a peaceful life. Among these four types of living, individuals who cultivate sympathetic joy can effectively address issues such as excessive selfishness, negative emotions, jealousy, autism, and dissatisfaction with life. These four factors play a transformative role, leading a person from a derogatory way of living to a sublime way, which is why they are referred to as Brahmavihara.

Furthermore, these four factors enable practitioners to attain heavenly realms, and for this reason, they are known as Brahmavihara. Moreover, through the practice of these four sublime ways of living, meditators can even achieve the five stages of meditative absorption (Pincamajhana) and reach the level of non-returner (Anāgāmi). Hence, these four factors are also called (Brahmavihara). According to Assistant Professor Dr. Sanu Mahatthanadull’s research, these four factors also constitute dhammasamādhi, as explained by Bhadantacariya Buddhaghosa: “cattāro brahmavihārā cāti ayaṃ dhammasamādhi nāma.”[9].

Among the four Brahmaviharas, the power of loving-kindness (Metta) has the initial capability to suspend human malice or ill will (vyapada) and it can also quell human anger. This is why loving-kindness is one of the four Brahmaviharas. Furthermore, loving-kindness (Metta) holds particular significance for harmony because it directly leads to the tranquility of the mind. In contrast, the most intense state of the human mind occurs during moments of anger. Anger has the potential to cloud people’s judgment and can lead them to harm both themselves and others. This perspective aligns with the story in the Dhammapada.[10], Despite possessing morality, living harmoniously with one’s neighbors can be challenging without loving-kindness for others. Therefore, the defining characteristic of loving-kindness is its contribution to the development of others, its capacity to diminish animosity, and its promotion of a positive outlook. Possessing these qualities, loving-kindness is referred to as Brahmavihara.

The second Brahmavihara in Buddhism is compassion (karunā), which naturally arises when witnessing the suffering, difficulties, or unfortunate situations of others. The essence of compassion (karuna) lies in resolving the difficulties of others, making it one of the four Brahmaviharas. More specifically, compassion embodies four qualities: (1) alleviating the suffering of others, (2) having a strong desire to assist others, (3) practicing non-violence, and (4) being a reliable support for disabled, displaced, or impoverished individuals. In direct contrast to compassion (karuna) is violence (vihinsa), so those who possess compassion are unlikely to exhibit violence, while those prone to violence tend to lack compassion and may appear cruel or heartless.

Compassion that is intertwined with romantic love or desire is not considered pure compassion; instead, it is referred to as fake compassion. True compassion should be devoid of any expectations or desires for reciprocation. In reality, compassion is about helping others without expecting anything in return, much like a fruit tree that offers countless fruits to all living beings without seeking anything in exchange. Therefore, compassion is an integral part of Brahmavihara.

The third Brahmavihara is Mudita (unselfish joy), which is the focus of the present research. It holds great importance in the contemporary world as human selfishness appears to be increasing day by day. As mentioned earlier, Mudita possesses four qualities: sympathetic joy (Pamodalakkhanā), non-judgment (Anissāyanarasā), alleviating unhappiness (Arativighātapaccupatthānā), and experiencing positive emotions regarding others’ success (Sattānam Sampattidassanapadatthānā). According to the research findings of Prof. Dr. Sanu Mahatthanadull, the first quality of Mudita is synonymous with great happiness. He explains, “In this research, the happiness that is mentioned here will be in a specific context of happiness in the dimension of mental and wisdom development, for example, pāmojja, pīti, sukha, etc. [11] However, as above explanation, having many qualities, Muditā also comprise in the Brahmavihara.

In Buddhism, the fourth Brahmavihara is equanimity (Upekkha), which holds significant relevance in contemporary issues related to human rights, equality, and diversity, as well as in addressing discrimination. The etymology of Upekkha implies the steadfast adherence to righteousness and justice without any bias or discrimination, which is why this aspect of compassion is also referred to as Brahmavihara. Equanimity (Upekkha) encompasses four distinct qualities: “remaining impartial, embracing an attitude of equality, eliminating feelings of love and hatred towards both friends and enemies, and recognizing the karmic dimension for all living beings.”[12]. In a comprehensive explanation of the qualities of Upekkhabrahmavihara, “standing in the middle” signifies making decisions without bias and avoiding corruption. “The view of equality” denotes maintaining an equitable mindset towards various aspects, such as wealth or poverty, social class, education level, kinship or non-kinship, and friendship or enmity. “Removing love and hatred” entails not favoring or disliking anyone, whether they are relatives or not, friends or enemies, when engaged in multiple tasks; everyone should be treated equally. The “dimension of karma” refers to a neutral perspective that arises when guiding or explaining to someone who is not following the right path. Over time, this neutral perspective recognizes that facing adverse circumstances is a result of their failure to follow the correct path.

Equanimity (Upekkha) stands in direct contrast to excessive self-centeredness and indifference toward others. It wholly rejects caste systems and discrimination. With these noble qualities, equanimity (Upekkha) is rightfully called a Brahmavihara. Therefore, as the above examination reveals, these four factors are interconnected and have relationships with each other. This is why they are collectively referred to as Brahmavihara. Individuals who embody these four factors lead lives characterized by sublime and noble living.

6. The Ways of Joyful Life and Daily Practice

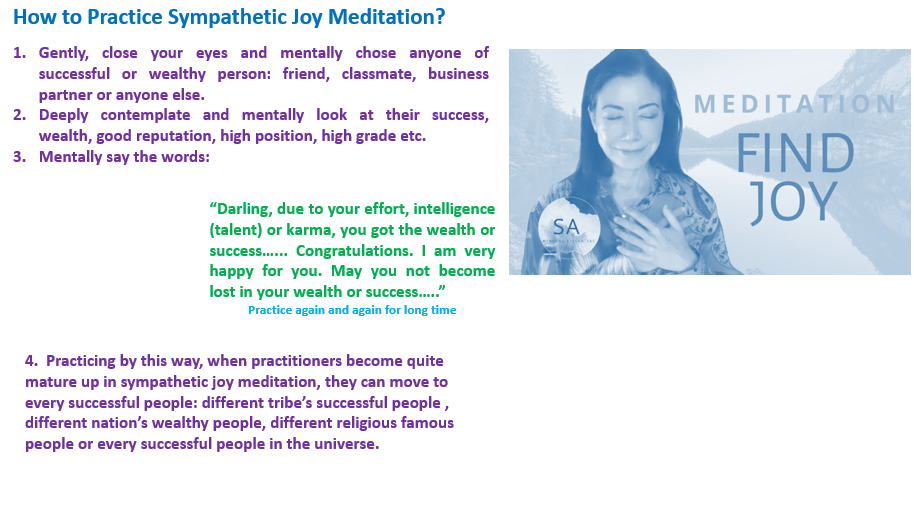

The method of practicing the Muditā meditational technique is crucial for reaping its effective benefits. Therefore, in accordance with the Visuddhimagga[13],For beginners of Muditā meditation, it is important to start by focusing on a loved one first. Once they receive good news related to this loved one, they can then extend their practice to include others, even their perceived enemies. If the meditator begins with a much-loved friend, they should contemplate, “My friend is so happy. Congratulations! May my friend not lose their wealth.” Additionally, meditators can engage in chanting in Pali language: “Modati vatāyam mayham sahāyo aho sādhu aho sutthu, yathāladdhasampattito mā vigacchatu.”

During this practice, meditators should also strive to cultivate positive emotional factors that are interconnected with Muditā meditation. The three most interconnected positive emotional factors of Muditā meditation are the adaptability of mental factors (kāyamudutā), the adaptability of the mind (cittamudutā), and compassion (karunā). Meditators can also extend their practice to include everyone using phrases like: “This being [person] is so happy. Congratulations! May this being [person] not lose their wealth,” or for multiple individuals: “May all beings not lose their wealth.”

In the context of self-compassion and sympathetic joy (Muditā meditation), meditators should take satisfaction in contemplating their own success or achievements, no matter how small, and continue cultivating the positive emotional factors as explained above.

When practicing Muditā meditation, it is important to evaluate the development of one’s meditational technique. Meditators can assess their progress by observing their reactions to good news or positive reputations of people they might consider as enemies. If their minds respond with jealousy or negativity, it indicates that their meditational skills are not yet fully developed. Conversely, if their minds respond with happiness and joy upon hearing about their enemy’s good news or reputation, it suggests that their meditation practice is progressing effectively.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this paper has explored the origins and impacts of common psychological problems, shedding light on their roots in negative thought processes and selfishness. It has delved into the realm of negative emotional factors, identifying those directly opposed to Muditā psychotherapy and elucidating their detrimental impacts.

Moreover, the paper has unveiled the core of psychological problems, demonstrating how misconceptions about self, body, and wealth lead to excessive self-love and destructive pursuits. In response, Muditā meditation has been introduced as a remedy, emphasizing unselfish joy and offering relief from emotional distress.

The interconnectedness of the four sublime ways of living, Brahmavihara, has been emphasized as a path to noble living and psychological well-being. Ultimately, this paper highlights the potential for transformation through the practice of Muditā meditation and the cultivation of positive emotions, paving the way for a harmonious and joyful life.

[1] Kvu. I-II. P. 492.

[2] Bhikkhu Bodhi, A Comprehensive Manual of Abhidhamma, (Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society press, 1993), p.83.

[3] Buddhaghosa’s Commentary, Atthasālinī, (London: Pāli Text Society, press, 1979), p.247.

[4] Asst. Prof. Dr. Sanu Mahatthanadull, Human Behaviors in Promoting Balance of Family according to Buddhist Psychology, Article of Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University, 38 Publications 7 Citations, (Online), Resource: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340629253, p.25.

[5] Vbh,A. p. 138.

[6] James W. H. Sonne1, Psychopathy to Altruism: Neurobiology of the Selfish–Selfless Spectrum, (Article in Frontiers in Psychology) DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00575, · April 2018.

[7] A. III. P.448.

[8] Buddhaghosa’s Visuddhimagga. THE PATH OF PURIPACATION, (London Pali Text Society press), p.363.

[9] Asst. Prof. Dr. Sanu Mahatthanadull, Theravāda Buddhist Practice and the Access of Happiness, Article of Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University, 37 Publications 7 Citations, (Online), Resource: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340629151 p.5.

[10] The commentary on the Dhammapada, Part I, (London Pali Text Society press, 1970) p.315.

[11] Asst. Prof. Dr. Sanu Mahatthanadull, A Conceptual Model of Bi-Dimensional Development for Happiness Access by Biofeedback Process, Article of Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University, 38 Publications 7 Citations, (Online), Resource: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341055628, p.380.

[12] Ibid., p.316.

[13] Buddhaghosa’s Visuddhimagga. THE PATH OF PURIPACATION, (London Pali Text Society press), pp.363-368.

Leave a Reply